Let’s start by gaining an overview of the different components of a website.

You probably already known about clients and servers. But how exactly do these fit into the context of websites?

The client

Most often, you are using a browser as a client for browsing a website. In grossly oversimplified terms, your browser is a piece of software that can fetch and render content, producing a visual and interactive output like the one you see on screen right now.1 To develop a website, we must learn how to create content in such a way that the browser renders the desired output. Today, we will see how to do this using HTML, CSS and JavaScript. Let’s start our adventure by writing a hello world page in HTML.

Create a file named webworkshop/index.html and open it with your favorite editor.

Paste the following into the file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Awesome title</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello HTML!</p>

</body>

</html>For now, all you need to know is that this is HTML and we have stored it in a file named index.html.

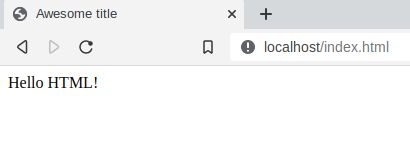

Make sure the Docker container is running (docker compose up -d) and open http://localhost/index.html in your browser.

You should see something like the following:

Congratulations! You have just written your very first webpage.

The browser somehow fetched the contents of index.html and rendered a page with the title “Awesome title” and the text “Hello HTML!”.

The server

We have now seen that the browser can read HTML and render it.

But what actually happened when you wrote http://localhost/index.html in the address bar?

As you might have already have guessed, this has to do with the local server the we have running.

Your browser used the http://localhost part of the URL to identify the server that we have running locally.

Then it contacted the server and requested the resource /index.html.

The server received this request, read the file index.html and sent the content of the file to your browser.

It is very common for web servers to behave in this way: you request some resource identified by a path (e.g. /index.html) and the server returns the contents of the file in it’s file system identified by that path.2

However, it is important to keep in mind that this is just one way that web servers can work and the can that the server can respond with anything it wants. It doesn’t have to read it from a file.

Some servers serve content that is purely generated from the information in the request or may even include random data (try visiting random.org).

Remember: the server can use any logic it wants to generate responses to requests. When we control the server, we control what the responses look like.

PHP is a programming language made specifically for creating webpages. The execution of code written in PHP is done entirely by the server and clients do not need to know (or care) that the server is using PHP. PHP has a number of built in constructs that make it convenient to perform common tasks related to websites. These include parsing request parameters, managing session data, integrating with databases and much more.

HTTP

Now that we have a basic understanding of what clients and servers are, we can examine how exactly they communicate.

HTTP is an application layer protocol that runs on top of TCP (or TLS using https) and it is the protocol that browsers use to communicate with web servers.

The HTTP protocol is specified in a series of RFCs and implemented by browsers and web servers.

Before you read the entire protocol specification, let’s quickly see what the requests from the browser actually look like.

We will be using a tool called netcat to start a simple client that will accept TCP connections.

nc -l 0.0.0.0 5000Now, if we navigate to http://localhost:5000/index.html in a browser, we will see something like the following printed to the terminal:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:5000

Connection: keep-alive

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/105.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8

Sec-GPC: 1

Accept-Language: en-GB,en

Sec-Fetch-Site: none

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, brThis is an HTTP request sent by our browser!

The line GET /index.html HTTP/1.1 tells us that the browser is requesting /index.html.

If we were a web server, we would probably read a file named index.html and send this back to the client.

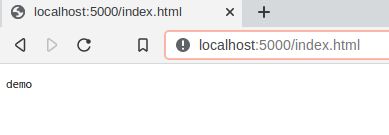

For now, let’s just answer with the text “demo” by typing:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 4

demoThe result is:

We just spoke HTTP! Cool huh? You will probably never have to hand write HTTP requests and/or responses, but it’s good to know that they exist and that they are being used to send information between clients and servers. There are several tools available for free that you can use to send customized HTTP request for debugging and testing. Postman is one such tool.

One more thing that we should know about HTTP before we proceed is that there are several types of requests methods.

Actually, there is only a handful of HTTP methods defined by the HTTP RFC. They are GET, HEAD, POST, PUT, DELETE, CONNECT, OPTIONS and TRACE.

Each of these have intended purposes that you should respect when creating HTTP services. You can read more about them in the RFC.

What we just saw is a GET request, which is intended to get a specific resource (identified by the URL).